My name is Emily Needle and I am a 3rd year History student at Newcastle University. I’m on a Placement in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library and this is my second Blog Post. I have been researching the famous polar explorer John Franklin, who lived from April 1786 to June 1847. The Great North Museum: Hancock’s new exhibition ‘Polar Explorers’ which inspired me to look at Franklin, opened on the 30th January 2016 and is aimed at families with younger children. Older readers might have heard of Franklin’s story. It is a famous and mysterious one which has become a nautical folklore legend and has been recounted in many folk songs and stories since his death.

Franklin was a British Royal Navy officer, and a famous explorer of the Arctic. He led his first expedition on unexplored coastline in 1819, after being chosen to chart the North coast of Canada. It was this expedition which gave Franklin the nickname “the man who ate his boots”, as the survivors who did not die of starvation from the long, hard winter journey were forced to eat their own leather boots as a source of nutrition. Between 1819 and 1822 he lost 11 of the 20 men in his party. An 1823 first edition of Franklin’s book ‘First Journey to the Polar Sea’ is held in the collection of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, which is located in the Great North Museum: Hancock Library. It contains his fascinating first-hand accounts, and also beautiful coloured sketches drawn by Lieutenant Back and Lieutenant Hood who were part of the expedition crew.

During this first expedition Franklin and his men faced many unimaginable challenges. His book describes how in October 1821 they trekked through one and a half feet of snow, the men despondent and gloomy. Lieutenant Hood was ‘reduced to a perfect shadow’ and was noted as very ill and feeble, and needing a walking stick to assist him. They saved a partridge for him to eat to try and restore his strength, but one of the men stole it in his own desperation.

‘The sensation of hunger was no longer felt by any of us, yet we were scarcely able to converse upon any other subject than the pleasures of eating.’ – ‘Franklin’s First Journey’ describing the extreme hunger they faced.

In 1823 Franklin took part in his second Canadian expedition which took him away from England until 1827. This journey is also captured in a book held in the Library, ‘Franklin’s Second Journey to the Polar Sea.’

However, it is his third and final voyage to the Arctic in 1845 that he is most famous for as it was the expedition from which he never returned. In the 1840s there was only 500 kilometers (311 miles) of unchartered Arctic coastline left to discover, and so Franklin and Captain Crozier set out in the summer of 1845 with 134 men, to attempt to chart the North-West passage through the Arctic to the Behring Strait.

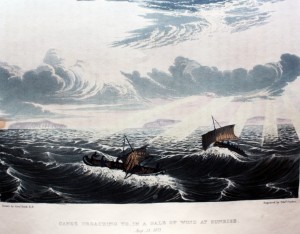

Their two ships were named the Erebus and the Terror and had been stocked with provisions for 3 years, but when nothing had been heard of them towards the end of 1847 people began to worry, and rescue missions were sent out. By 1850, a total of 15 vessels had been sent in search of John Franklin and his ships. They all failed to find any evidence of a ship, or of the 145 men.

So what did happen to John Franklin in the Arctic and why is his disappearance such a mystery?

Whalers off the coast of Baffin Bay in Greenland reported last seeing Franklin’s ships during the summer of 1845. In her desperation to find her husband, Franklin’s wife, sent out five ships and ordered for cans of food to be left on the ice in her hope that he was still alive and would find them. A group of Inuit hunters told Scottish explorer John Rae in 1854 that Franklin and his crew had all perished. Later they described that they had sighted white men from a distance wandering in the freezing wilderness over a few months in 1845.

By 1854 it was clear that Franklin was not going to return. The ships that set out after this date were to search for remains, or any evidence that might shed light on what had gone wrong. Between 1850 and 1855 Captain Richard Collinson wrote an account of his voyage to find Franklin on the HMS Enterprise. He discovered a small piece of wood that was almost certainly part of a cabin door from one of Franklin’s ships. The Enterprise managed to go farther than any of the other ships at the time into the Arctic on the route than Franklin had journeyed. Collinson poetically described the dangerous life in the Arctic Franklin and the other men had faced, and which had cost them their lives:

‘[The] constant struggle for life against bitter elements… in the numbing cold; in the dead silence of space where scarcely the foot of man or beast has trod since it was created…’

In 1981 it was revealed by forensics that an examination of bones exposed knife marks, indicating that the crew had resorted to cannibalism in their extreme hunger. Some of these bones were discovered as far as mainland Canada so the crew had clearly roamed far in search of help, but had still been hundreds of miles away from western civilisation. Anthropologists believe that all the crew had died by 1849, mostly from pneumonia, starvation, scurvy and tuberculosis. Post-mortem examinations carried out also picked up lead poisoning, perhaps from the ship pipes or leaks in the canned food. A note found written by John Franklin on Beechey Island indicates that he may have died on 11th June 1847. His resting place has never been found. Experts think that the Terror and Erebus became trapped in some ice near King William Island in September 1846 and could not break free.

In 2014 a huge breakthrough was made by Parks Canada with the discovery of one of the two ships– The Erebus. The clear sonar image of the ship can be seen below: it had been well-preserved in the cold, dark climate of the sea bed, only 11 metres below the water level.

The wreck of HMS Erebus discovered on the sea bed of Queen Maud Gulf in Northern Canada by Parks Canada marine archaeologist Ryan Harris. Photograph : Parks Canada AP

This discovery verified the Inuit’s’ word in the 1850s, who had previously been dismissed as savages when they said they had seen the ship near where it was eventually discovered in 2014.

Franklin’s story has gone down in history, in the words of his biographer Andrew Lambert, as “a unique, unquiet compound of mystery, horror and magic”. The path through the Canadian waters to the Pacific that Franklin set out to chart was not completed until 1906, and it is due to the effects of global warming that the Arctic is more open to explorers and scientists today than it was 150 years ago when Franklin set out. The other ship on Franklin’s voyage, The Terror, has never been found. And as to whether his body is on the Erebus, this remains to be seen.

Lady Franklin’s Lament was written in around 1850 and tells the tale of a sailor who dreamt of Lady Franklin lamenting for her lost husband. You can hear a version of this sad but haunting piece of music by using the following link.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiXD6kH7sXI

The Great North Museum: Hancock Library is located on the second floor of the Museum. It is free to use and open to everyone. You can arrange to view first editions of Franklin’s first two journeys to the Arctic, and also Sir Richard Collinson’s account of the expedition of 1850 – 55 that he conducted in search of Sir Richard Franklin’s ships. Also available are copies of Robert F Scott’s books on his polar expeditions and many other fascinating works that are linked to polar exploration. Further information about the Library is available by using the following link.

https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk/collections/library-and-archives

2 Responses to John Franklin – The mystery of the Polar explorer