Making collections as accessible as possible, is what Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums strive for. A pioneer in this field was Charlton Deas, a former curator at Sunderland Museum. From 1913, John Alfred Charlton Deas, organised several handling sessions for the blind, first offering an invitation to the children from the Sunderland Council Blind School, to handle a few of the collections at Sunderland Museum, which was ‘eagerly accepted’.

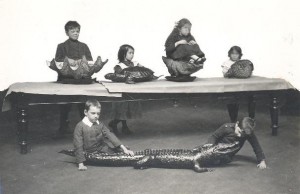

A group of blind children feeling the stuffed walrus at Sunderland Museum, headed by J. A. Charlton Deas.

In a document written by Charlton Deas titled “What the Blind May ‘See’: Some Museum and Other Experiments in Tactile Sight”, he speaks of a teacher called Mr G. I. Walker who expressed the difficulty of blind children in understanding the concepts of size. He stated:

“however carefully the children were informed that their small model of a cow was only one-fortieth the size of the real animal, they were unable to think of the cow as anything larger then the model.”

This is because unless they have had actual tactile contact with something, there is “no standard of size, form and texture” to relate it to. Charlton goes on to share an instance that he came across when a young blind boy had recovered his sight after having an operation. He said:

“For several days following, he went about in a state of surprise and fear, for almost everything which he had not frequently touched, differed in size from his recollections of seven years previously.”

The sessions that were offered to the children from the blind school were so successful that Deas went on to develop and arrange a course of regular handling sessions, extending the invitations to blind adults. These generally ran on Sunday afternoons between 2.30 pm and 5.30pm, as this was the most convenient time for the visitors. It also gave them more privacy, as it was closed to the general public on Sundays.

Descriptions of the room arrangements were given and the names of the people attending were announced, this was to give the visitors a better idea of their surroundings and company, as “lineal measurements convey little more than to state that a place is “as long as a piece of rope!” and “Measurements which are difficult of mental visualization to a sighted person, are more so to a blind one.”

The first session concentrated on paintings and drawings, each thoroughly described to the visitors, who then were able to ‘see’ through touch, by feeling for the outlines made by the brushstrokes, so that they could identify the main features of the painting.

1913 Sunderland Museum. A group of blind children from Sunderland School for the blind and their teacher.

The following Sunday, Deas devoted the session to natural history objects. Directed by a guide, the blind visitors examined each specimen and descriptive labels were supplied, to give them extra knowledge of the object and subject surrounding it. Charlton Deas stated:

“To them, their fingers are eyes; fingers which are much more capable than the less sensitive ones of sighted people. This careful guiding of the hands is by no means simple. When it is remembered that one must explain each interesting point simultaneously with the touch, and that only one person can be satisfactorily dealt with at a time.”

Dr. H. K. Wallace (a local zoologist) gave a brief lecture for the first natural history Sunday session, which visitors examined a chimpanzee, lion, lioness and cubs, tiger, polar bear, badger, otter, wolf, seal, walrus and many others.

The next handling Sunday session was dedicated to reptiles, being shown a crocodile, turtle, python, snake, blue shark and various fish.

The blind visitors are handling the reptile specimens at Sunderland Museum, including the crocodile and shells.

Birds, nests and eggs were spoken about in a lecture delivered by Miss Norah March, B.Sc on the following Sunday and specimens such as an eagle, barn owl, kingfisher, cuckoo, swan, pelican and several others were handled.

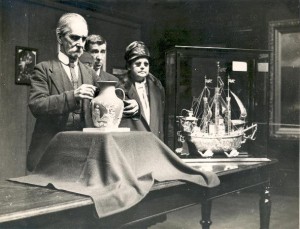

1913 Blind adults at Sunderland Museum listening to a short lecture before examining a human skeleton.

“An instructive explanation of the human skeleton was given by Alderman Dr. Gordon Bell, who brought his subject up-to-date with a brief account of some recent developments in osteology.”

Miscellaneous objects were handled on the fifth Sunday including swords, daggers, rifles, pistols and spears.

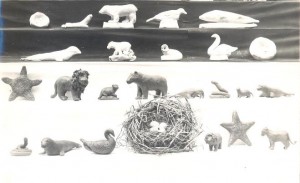

Some of the children produced clay models based on the collections that they had handled at the museum. Ranging from 8 to 15 years old, these blind children created these models 5 weeks after their visits, some without any previous experience in handling clay. These were then displayed at Sunderland museum in cases along with photographs of their visits.

The work that J. A. Charlton Deas carried out whilst at Sunderland Museum is much to be admired. His interest in the education of the blind and his determination to assist in their development, had a great impact on how they now viewed the subjects. In a letter from the childrens teacher, Mr. Walker wrote:

2 Responses to John Alfred Charlton Deas