This iconic image of Turbinia conveys an impression of speed like no other. The rearing stem, the massive bow wave and the foaming ‘rooster’s tail’ wake all play their part, but perhaps the most unusual element for a maritime photograph is the figure braced against a bar on the conning tower. It is as if a wing walker from the age of flight has intruded on the scene. The man leans forward to resist the near gale while with his left hand he pulls on a cord that operates Turbinia’s steam whistle. He looks towards the camera but his face is buffeted by the wind and his hair streams back off his forehead.

So who is the man on the conning tower?

John Maxtone Graham in his book, ‘Queen Mary 2 – The Greatest Ocean Liner of Our Time’, captions the image, ‘Sir Charles Parsons on the flying bridge of his little Turbinia, the world’s first turbine-driven vessel’ (1). On the other hand Ken Smith in his 1996 book, ‘Turbinia – The Story of Charles Parsons and his Ocean Greyhound’ writes of the same image, ‘Turbinia works up to over 30 knots on one of her runs. Her captain and lookout, Christopher Leyland, stands atop the conning tower’ (2).

Rollo Appleyard’s 1933 biography of Parsons makes it clear that Parsons was usually at the engine-room controls, in the engine-room cab. ‘On board the Turbinia, Parsons generally took charge of the controls in the engine-room assisted by two engineers’ (3). In another passage he refers to the difficulties faced by the stokers caused by the forced draught fan being driven by the central turbine shaft. The faster the engine rotated the more work the stokers had to do to keep up. Appleyard says that the stokers ‘sometimes wondered whether Mr Parsons at the controls had them too much at his mercy, and whether his great conception had included a fan to impart liveliness to their movements’

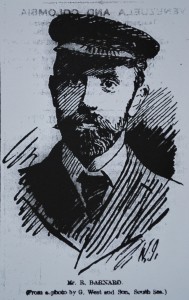

In the same section we are also told that: ‘Steering and conning-tower operations were undertaken by Mr. Barnard, who was at that time a manager.’ Much of the trials work with Turbinia took place in the River Tyne because the North Sea was not usually calm enough for her speed trials. In the river there was almost a straight mile alongside Northumberland Dock. When there was no traffic Turbinia would utilise this section of the river, accelerating quickly before cutting her speed just as rapidly at the end of the run. She was breaking the speed limit but the River Tyne Commissioners took a benevolent view of Parsons’ experiments. Robert Barnard was a marine engineer and naval architect. He was a key figure in the success of Turbinia and the further development of the marine steam turbine. Barnard assisted in the designs of the “Turbinia” and oversaw her construction. He supervised the construction of the “Viper”, the “King Edward,” and also the “Cobra” (4). Although not spelt out by Appleyard, there is an implication that Robert Barnard took command of Turbinia during these runs in the river.

For official speed runs Turbinia needed to go beyond Tynemouth Piers into the North Sea. She would carry out pairs of runs in opposite directions on the official Hartley measured mile, to the north of the Tyne. Her mean speed could then be calculated. On those occasions C. (Christopher) J. Leyland was usually aboard and took command of the vessel.

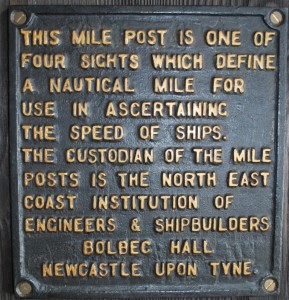

Plate from one of the four posts defining the Hartley Mile, the measured mile used for Turbinia's speed trials TWCMS : E3100

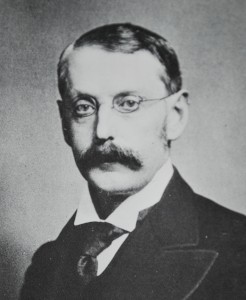

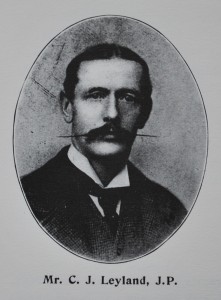

Christopher Leyland had been for some years in the Royal Navy before inheriting a large estate in Wales. He moved to Haggerston Castle in Northumberland and was both a friend and financial backer of Parsons. He was a director of the Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company (5). We know from Leyland’s own account that, in addition to being the captain of Turbinia, he also steered and acted as lookout. Leyland switched between roles as circumstances required, but on at least one important occasion we can be certain that he was positioned on the conning tower, acting as captain and lookout.

At the Spithead Review of 1897 Leyland had responded to a request from Prince Henry of Prussiato show a turn of speed. As Turbinia worked up to full power a vedette – a small naval boat – tried to head her off. Turbinia just managed to steer a course astern of the vedette, while the vedette’s crew dashed into her bows and her Lieutenant unbuckled his sword, expecting to have to swim. To quoteLeyland, “he evidently spoke to me, and I said something to him, but as we were passing at nearly 45 knots, it may have been just as well that out impromptu remarks did not carry”. ForLeyland to have been able to respond under such circumstances he could not have been down below in the wheelhouse, he must have been positioned on the conning tower (6).

The two probable candidates for the man on the conning tower are Christopher Leyland and Robert Barnard. It seems highly unlikely that it could have been Charles Parsons. Leaving aside our knowledge of Parsons’ role as chief engineer of Turbinia we also know that as an adult he always wore glasses and would have struggled to see anything after a few moments exposed to the salt spray. The man on the conning tower in the photograph does not look like Parsons and is not wearing glasses.

The photograph was taken by Alfred J West of Southsea, a marine photographer and pioneer cinematographer. In his unpublished autobiography ‘Sea Salts and Celluloid’ (1936) he recalled how he successfully photographed Turbinia at the 1897 Spithead Review and was subsequently invited by Parsons to come to Newcastle to photograph and film her on the Tyne (7).

West’s iconic image is not of Turbinia at Spithead, nor of her on the Tyne, but almost certainly of her in the North Sea, just off the mouth of theTyne. There are no landmarks in shot to anchor the image to the North East but there is a pretty good clue in the background. If you look on the horizon, midway between bow and conning tower and just above the safety rail, there appears to be a Tyne paddle tug, with her foresail set, towing two fishing boats. This would have been a familiar sight off the North East coast in the 1890s, as the adoption of steam-powered fishing boats was just starting, and tugs frequently towed herring boats out to the fishing grounds.

The open sea location for the image would seem to make Leylandthe favourite for the man on the conning tower. We know he took command for the official sea trials on the Hartley Mile. To capture the best photograph Turbinia would have to be steered at full speed very close to the photographer’s launch. Under those circumstances I doubt that the duties of captain and of lookout would have been entrusted to anybody other than Leyland.

Images of Leyland exist and they can be compared with the Turbinia at speed image, although it is not easy. One can’t draw too many conclusions about the appearance of a man whose face is being buffeted by a 40 mph wind! Leyland’s waxed moustache is a striking feature of his formal portraits but one imagines, even if he bothered to wax his moustache on trials days, the effect wouldn’t have survived the wind and spray. However, the basic geometry of the man’s face appears to match that of Leyland.

Unlike Leyland, the alternative candidate, Robert Barnard, did not live to reminisce about Turbinia in his old age. Barnard was drowned when the torpedo boat destroyer Cobra broke in half and sank in heavy weather in the North Sea on September 18th 1901 while on passage from the Tyne toPortsmouth. In total 67 men were drowned with only 12 being saved. Barnard was the manager of the Parsons’s Turbine Company Ltd., and the senior man of the 24 Parsons employees aboard, of whom only 2 were rescued (8). He was 35 years old and left a widow, Mary, a daughter of 12, also Mary, and a son of 8, William (9).

The Newcastle Evening Chronicle of Friday 20th September covered the tragedy and published a print of Barnard taken from a photo by G. West and Son, of Southsea, Alfred J West’s company. There is a distinct possibility that Barnard’s portrait photograph was taken when West visited the Tyne to photograph and film Turbinia and therefore it may be contemporary with the famous image of Turbinia at speed. And here perhaps we have a real stroke of luck in our search for the identity of the man on the conning tower. In the Chronicle print Robert Barnard is sporting a full beard! In contrast the left hand side of conning tower man’s jaw is clearly clean shaven.

The man on the conning tower is almost certainly Christopher Leyland. It is not Charles Parsons because he typically stationed himself at the engine room controls. It could be Robert Barnard because he took charge of the conning tower and steering when Turbinia was being worked up in the Tyne. However, the open sea location for the photograph and the clean shaven jaw of conning tower man make it unlikely that it was Robert Barnard. In West’s iconic photograph of Turbinia at speed, conning tower man is Christopher J Leyland.

REFERENCES

1. Maxtone-Graham, John, Queen Mary 2 – The Greatest Ocean Liner of Our Time, P106, Bulfinch Press,New York, 2004.

2. Smith, Ken, Turbinia – The Story of Charles Parsons and his Ocean Greyhound, P4,TyneBridgePublishing,Newcastle, 1996

3. Appleyard, Rollo, Charles Parsons – His Life and Work, P105 Constable & Co.,London1933

4. Transactions of theNorth East CoastInstitution of Engineers and Shipbuilders, Vol. XVIII (1901-2), P359

5. A Dictionary of Edwardian Biography – Northumberland, Edinburgh 1985. A reprint of the biographical part of “Northumberland at the Opening of the Twentieth Century”, first published in 1905

6. Leyland, Christopher, Heaton Works Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1 (June 1935), P25-32, “Turbinia” Jottings

7. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_John_West

8. Newcastle Evening Chronicle, September 20th, 1901

9. 1901 Census Return, Northumberland

15 Responses to “Turbinia” at speed – but who’s on the conning tower?