This photograph of the devastation of the Basque port of Bilbao in April 1937 was taken by Captain Still of the Newcastle ship Hamsterley, on a mission to take food to the beleaguered city and rescue refugees during the Spanish Civil War (North Mail, May 11th).

I’ve told some of the story of the involvement of Newcastle ships in two previous blogs – Newcastle foodships rescue Basque refugees in the Spanish Civil War; Newcastle foodship crew witness the devastation of Guernica bombing in the Spanish Civil War. This blog widens the story, with more details about the difficult experiences of the crews.

Eighty years ago, the crews of ships from Tyne and Wear found themselves caught up in the Civil War in Spain (1936-39), dodging shells, mines and bombs. The North East of England had a strong trading relationship with the Basque region of northern Spain, exporting coal and importing iron ore. North-East sailors also worked on many other ships trading coal to Spain. Some of the captains and crew were keen to help the Basque people, others were just doing a job, and some would rather have avoided the dangers of the warzone.

Dangers to Ships and Crews

Early in the conflict, Nationalist warships began stopping British ships to check they were not carrying any materials that could help the Republican war effort. The British ships’ crews sometimes saw floating mines and experienced air raids, often quite close to their ships. The most dangerous incident was when the Newcastle ship Blackhill was shot at near Bilbao in March, prompting official British protests. Until a test case at the South Shields Court of Referees in March 1937, seamen didn’t have a choice about sailing to the warzones if they didn’t want to lose unemployment benefit.

In April 1937, the situation for ships’ crews sailing to northern Spain became more difficult as the Nationalists intensified the war effort in the Basque region.

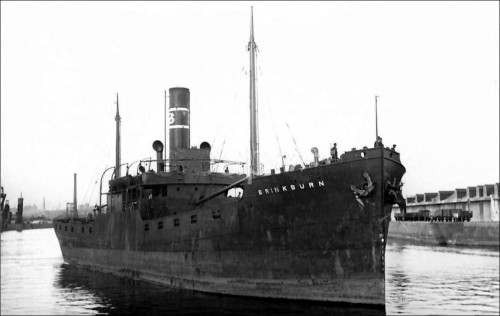

Wear Ships Coquetdale and Brinkburn at Bilbao

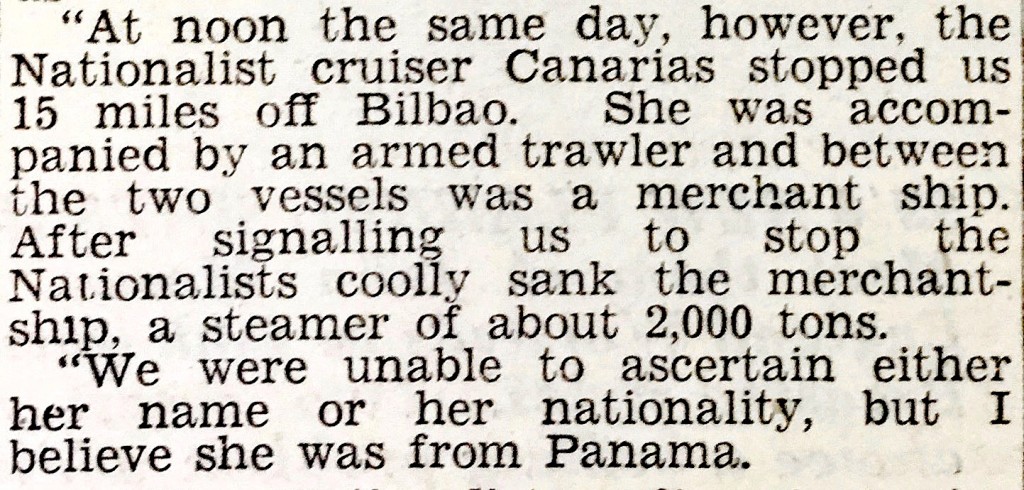

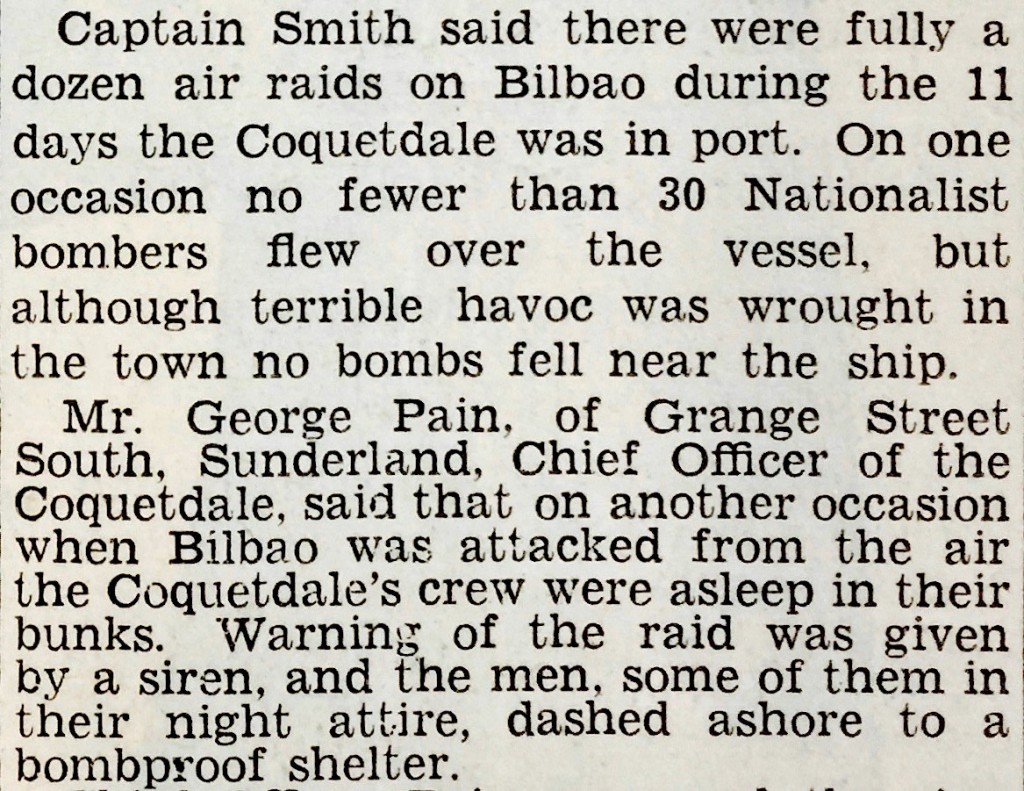

In very early April 1937, the Wear ships Brinkburn and Coquedale (Consett Iron Company) arrived in Bilbao with food from Antwerp. (This photo of the Coquetdale can be viewed in higher resolution on the searlecanada website.) Speaking to the North Mail on their return (22nd April), the Sunderland skipper of the Coquetdale, Captain Charles Smith, described their voyage. The ship had already been stopped once when they witnessed a distressing event:

Coquetdale had arrived too late to see whether the ship’s crew had been taken off. Captain Smith continued:

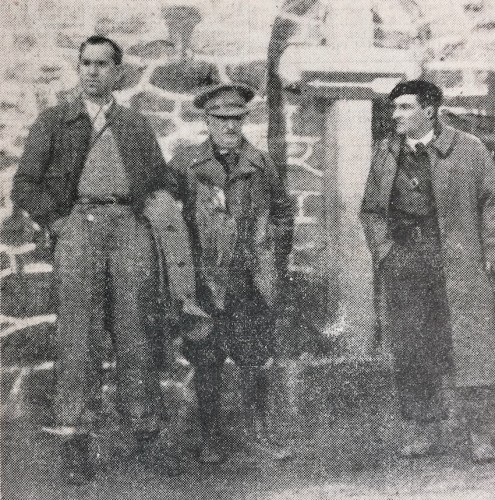

The Couetdale and crew, and Captain Smith (right) were pictured in the North Mail (April 22nd, p7) when the ship berthed at Tyne Dock:

The Coquetdale’s sister ship Brinkburn was also at Bilbao at this time, having brought potatoes from Antwerp.

Captain Collinson of the Brinkburn also described frequent air raids at Bilbao, commenting that “One bomb dropped in the water 300 yards astern of us while we were lying at the quay.” (Sunderland Echo, April 20th). The North Mail (April 21st) continued Captain Collinson’s story, describing how the population was desperately short of food:

Captain Collinson of the Brinkburn also described frequent air raids at Bilbao, commenting that “One bomb dropped in the water 300 yards astern of us while we were lying at the quay.” (Sunderland Echo, April 20th). The North Mail (April 21st) continued Captain Collinson’s story, describing how the population was desperately short of food:

Blockade of Bilbao and Santander

While Coquetdale and Brinkburn were at Bilbao, Franco imposed a blockade, intending to starve the Basque city of food and materials.

Brinkburn was the last ship into Bilbao before the blockade, said Captain Collinson (Sunderland Echo, April 21st). Having rapidly loaded her cargo, she was also the first ship out, fortunately without a problem, returning to Sunderland on April 20th:

“When we left after a stay of five days a number of insurgent warships came and had a look at us, but they did not interfere…”

Coquetdale similarly made it out of Bilbao without incident, but when the ship finally returned to the North East, several of the crew decided they wouldn’t make another trip to the warzone.

Franco’s blockade of Bilbao and Santander and other Basque ports began on April 6th. It was enforced by the warships Almirante Cervera, Espana, and Canaries, with the large armed trawler Galerna and a flotilla of smaller armed trawlers. Later, two submarines joined the blockade, and Franco could also call on a large airforce. On April 14th, the North Mail mentioned that, “Some idea of the dangers of taking legitimate cargoes to Spain can be gathered by the jump in the freight rate from the Tyne to Bilbao from about 7s. to 15s.” The seamen got a bonus of 50% of wage for 24 hours either side of being port, raised to double pay from May 17th.

British Ships Blocked

The population of the Basque capital Bilbao was swollen by refugees from surrounding towns and the land supply routes were cut off. Food was in short supply. Immediately after Franco’s announcement on April 6th, the (Wear-built) London steamer Thorpehall got through. Nevertheless, the British government advised ships to stay away, fearing that the approaches to the Basque ports were heavily mined.

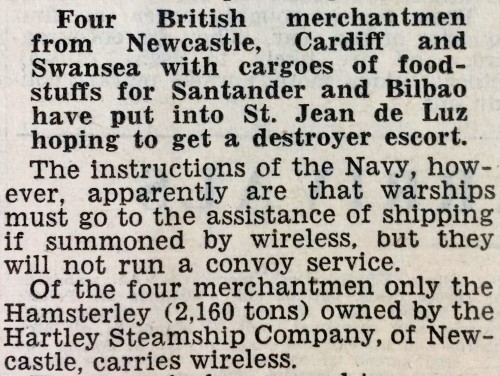

However, the Newcastle ship Hamsterley was already on her way to Bilbao, having left Antwerp with a cargo of peas and beans on April 3rd (North Mail, April 12th). After receiving an Admiralty warning that protection was not guaranteed, Captain Still retreated to the French port of St Jean de Luz. Hamsterley joined several other British ships waiting in the hope of Navy assistance to get through the blockade (North Mail, April 10th):

The Nationalist cruiser Almirante Cervera sent out a warning that “any foreign vessel approaching the Spanish coast would be sunk or seized”. The food ships continued to wait.

The Nationalist cruiser Almirante Cervera sent out a warning that “any foreign vessel approaching the Spanish coast would be sunk or seized”. The food ships continued to wait.

Bilbao Blockade Runners Hamsterley and Stanbrook

However, after the Welsh ship Seven Seas Spray successfully made a solo dash from St Jean de Luz to Bilbao with food, arriving on April 20th, the British government authorised the Navy to give more protection to British ships breaking the blockade. Hamsterley (pictured on Wrecksite) was the next ship to run the Bilbao blockade, in a small convoy with Stanbrook, which had sailed from Blyth, and the MacGregor. They arrived at Bilbao on April 23rd.

The three ships Hamsterley, Stanbrook, and MacGregor had left the French port of St. Jean de Luz the previous night. As dawn broke, they were intercepted by an armed Nationalist trawler, which fired a shell between the Hamsterley and the MacGregor. But the British flagship Hood and the destroyer Firedrake came to their aid. The blockade runners were big news in Britain, and Hamsterley had a Daily Express reporter on board. He gave a vivid description of their journey as they neared Bilbao (Daily Express, April 24th):

We were now leading the convoy, but we had gone only a few yards when the trawler, the Galerna, fired right across our bows. The shell skimmed across the deck very low and plunged into the sea a bare fifteen yards away. Captain Still cursed aloud, and banged his fist on the bridge rail. “Stop her, quartermaster!”

Another signal fluttered from the destroyer’s mast: “Proceed, Hamsterley.” Captain Still fairly bellowed through the megaphone to the Stanbrook, just astern: “Come on, my lads! Follow me into Bilbao.” … 8 a.m. – Shell from shore battery has just fallen a bare six feet short of the Galerna. Galerna turned in her own length, and, dodging between the Hamsterley and MacGregor, scuttled off to safety…

The British ships were given a tremendous welcome when they berthed up in the town this afternoon. They arrived in the middle of an air raid, but hundreds of people came from their shelters to cheer the blockade-runners. The raiders came in batches of nine; since yesterday they have dropped 500 bombs.

Captain Still of Hamsterley (wearing cap) brought this photograph back from Bilbao, where he was visiting an army factory with the Basque Minister of Marine (far left), Captain Roberts of Seven Seas Spray (second left), the President of the Basque Republic (in beret) and Captain Jones of the MacGregor (far right) (North Mail, May 11th).

The newspaper also later published Captain Still’s photograph of the aftermath of one of the air attacks on the city. The crew of the Hamsterley were mostly from South Shields (listed at the end of the blog). On this ship, the firemen, who had the hot and tiring job of stoking the boilers, were drawn from South Shields’ Yemeni community.

The newspaper also later published Captain Still’s photograph of the aftermath of one of the air attacks on the city. The crew of the Hamsterley were mostly from South Shields (listed at the end of the blog). On this ship, the firemen, who had the hot and tiring job of stoking the boilers, were drawn from South Shields’ Yemeni community.

The Stanbrook, which accompanied the Hamsterley, was built by the Tyne Iron Shipbuilding Company. She had sailed from Blyth to Antwerp on about April 10th to take on her cargo of food. She had several crew members from Blyth and Tyneside, reported the North Mail (April 24th) (listed at the end of the blog).

Tyne ships to Bilbao: Stesso, Sheaf Garth, Sheaf Field, Blackhill and Consett

More ships followed including the Newcastle coal ship Stesso, manned by Tynesiders, which arrived on April 25th. The Sheaf Garth (Sheaf Steam Shipping Company, Newcastle) arrived at Bilbao on April 26th, and her sister ship Sheaf Field entered port three days later, carrying food. One of the ships waiting to run the blockade was the Newcastle ship Blackhill, said the paper (North Mail, April 24th, 26th, 27th & 30th).

The master of the Sheaf Field was Captain R. Arnott of South Shields, and there were several Tynesiders on board. The second steward, Ernest Hawkins of Hull, told the North Mail (May 12th) how the ship was rocked by explosions from bombs aimed at oil tanks on the banks of the river.

The crew helped load the cargo of iron ore themselves in an effort to get away quickly, and the ship returned to the Tyne on May 11th. Sheaf Field had spent 2 months in the Spanish war zones, and had experienced air raids in every Spanish port they’d visited – Valencia, Barcelona, Tarragona, Portugalette and Bilbao. The second steward Ernest Hawkins also told of the acute food shortage in Bilbao:

The Consett (Consett Iron Company) arrived in Bilbao right at the end of April. The captain had intended to dock at Santander but was confronted by the Nationalist battleship Espana, which threatened to fire on her. Consett had no radio to call for help, but fortunately the British destroyer Forrester came to her aid. A crew member later told the Sunderland Echo (May 7th) that the situation at Bilbao was serious:

The evacuation had not started and hundreds of citizens both rich and poor crowded the quayside. “We gave them everything we could and any food left lying about they stole from the ship.”

Just after the crew listened to a radio broadcast of the Cup Final football match (Sunderland won) on May 1st, there was an air raid. Many of the crew joined people sheltering in “dugouts … underneath the slag heaps at the quayside”, said the Consett sailor:

“I had a child who was weeping in my arms, and we tried to cheer him by singing sea shanties.”

…“Eventually we sailed from Bilbao thinking our adventures had finished, but 36 miles out we were stopped by an armed merchant ship. It was a tense situation and I must confess I was scared.” The guns on board her, he continued, were all manned, and for an hour she circled round the Consett, no one knowing what was going to happen.

The steamers Blackhill, Sheaf Field and Consett all took part in the refugee evacuation of Bilbao in May together with Hamsterley and Backworth.

Backworth Relief Ship to Bilbao

In Britain, the Spanish Relief Fund (set up to provide humanitarian aid to either side) co-ordinated appeals to send food and medical supplies to Bilbao. The ship chosen was the Backworth, which loaded at Immingham near Hull (Backworth was built on the Clyde, and this photo is from the website Clyde Built Ships). Before Backworth left, the North Mail (April 24th) reported:

The North Mail also gave the names of other Tyneside crew members (see end of the blog), who had signed on at Newcastle. On April 28th, the ship began a nail-biting approach into Bilbao, chased by Nationalist ships, (the dramatic events are described in my previous blog – Newcastle foodships rescue Basque refugees in the Spanish Civil War). Ships’ captains worried that their ships might be trapped if the Nationalists took the port while they were anchored there.

Backworth was a key ship in the British refugee-evacuation programme in early May and afterwards. Captain Russell of the Backworth telegraphed the North Mail (May 7th) to outline his plans:

Knitsley at Santander

Newcastle steamer Knitsley’s encounter with Espana outside Santander was even more momentous than the confrontation Consett had. The Sunderland Echo reporter got the opportunity to talk to the crew when the ship docked at Sunderland with iron ore (Sunderland Echo, May 6th). (The ship is pictured at Tyne Dock on a separate occasion.)

Newcastle steamer Knitsley’s encounter with Espana outside Santander was even more momentous than the confrontation Consett had. The Sunderland Echo reporter got the opportunity to talk to the crew when the ship docked at Sunderland with iron ore (Sunderland Echo, May 6th). (The ship is pictured at Tyne Dock on a separate occasion.)

On Friday, the Knitsley loaded with minerals disregarded signals to stop given by the Spanish insurgents battleship Espana and the destroyer Velasco outside Santander.

The insurgent vessel fired on the steamer, but Government planes went to her rescue and the Espana was sunk. The Knitsley entered Santander in safety… Captain Robinson was quite cheery this morning … [but] Another member of the crew said they had had a terrifying voyage.

Following this trip, 11 members of the crew refused to sail on another voyage to Spain if they didn’t get more than the agreed warzone bonus of the time. At court in Sunderland in June, they were convicted of conspiring to impede the ship’s progress and fined 40 shillings each (North Mail, June 18th). During the trial, the captain testified that the trip had been been much more dangerous than a normal commercial voyage:

Hamsterley and the last days of Republican Bilbao

The Newcastle ship Hamsterley continued to sail to Bilbao to load iron ore. The ship last left the city on June 13th, 6 days before the city was occupied by the Nationalists. While in Bilbao, Captain Still took this photograph of the President of the Basque Republic reviewing his troops. It was published in the North Mail on June 19th, the day after Hamsterley docked on the Tyne, together with an interview:

The Newcastle ship Hamsterley continued to sail to Bilbao to load iron ore. The ship last left the city on June 13th, 6 days before the city was occupied by the Nationalists. While in Bilbao, Captain Still took this photograph of the President of the Basque Republic reviewing his troops. It was published in the North Mail on June 19th, the day after Hamsterley docked on the Tyne, together with an interview:

Shortly before the city fell, the Newcastle steamer Alice Marie had arrived from Blyth with a cargo of food, coal, ambulances, motor-cycles and medical equipment. The ship subsequently left port with a part-load of iron ore plus 500 refugees. The North Mail (June 21st) published an account by the second engineer F.A. Snaith, given in a letter home to his wife in South Shields:

Bilbao fell to the Nationalists on June 19th, and Santander followed in August 1937. The Civil War finally ended in 1939.

My reading of newspapers finishes in 1937, and is mainly about the steamers voyaging to northern Spain (prompted by the 2015 exhibition British Art and the Spanish Civil War at the Laing Art Gallery). The war continued in southern Spain, and North East sailors were involved in dangerous situations there. The ships included the Newcastle steamer Hebburn, which spent 4 months in Spanish ports, experiencing severe air raids at Valencia, Barcelona and Santander, before returning to the Tyne on May 14th 1937 with iron ore from Castro Urdiales, a port near Bilbao. The Tyne-built destroyer H.M.S Hunter, with a Sunderland captain, Commander Scurfield, and some Tynesiders among her crew, hit a mine off Valencia on May 13th 1937. The ship had significant damage and several men died (North Mail, May 15th and 17th). Eleven days later, the Newcastle steamer Greatend, while unloading grain, was hit by shrapnel in a Nationalist air raid at Almeria and nearly sunk (North Mail, May 25th). In addition, the Thorpehall (which had a Sunderland master, Captain Andrews) was sunk in an air raid in May 1938 near Valencia.

How Britain learnt lessons from air raids in Spain

One result of the terrible air-raids in Spain was that air-raid precautions planning started in Britain in case of war with Germany. In April, when construction started on a new block of flats, Moor Court in Gosforth, it including a “bomb-proof shelter” in the basement (North Mail, April 5th). Newcastle council also set up a plan for 5,000 volunteer civilian air-raid personnel (North Mail, June 10th).

One result of the terrible air-raids in Spain was that air-raid precautions planning started in Britain in case of war with Germany. In April, when construction started on a new block of flats, Moor Court in Gosforth, it including a “bomb-proof shelter” in the basement (North Mail, April 5th). Newcastle council also set up a plan for 5,000 volunteer civilian air-raid personnel (North Mail, June 10th).

*****************************************************

Backworth: North Mail 24th April 1937 p3: The crew of the Backworth includes; A. Goodfellow, first mate, Tunstall Road, Sunderland; George Lilie, second mate, Broadway, Cullcoats; C. Spence, A.N., Brderick Street, South Shields; C. Piggofrd, third engineer, Elmwood Street, Sunderland; Janir Mohammed, fireman, Thrift Street, South Shields; F. Sagar, steward, Hyde Street, South Shields; E. Brockie, second engineer, Edenhouse Road, Sunderland; G. Whitelock, A.B., Cleveland Road, Sunderland; Harold Renwick Bottomley, A.B., Ashgrove Avenue, South Shields; J. Wilson, ordinary seaman, Viceroy Street, Seaham Harbour; A. Felgate, steward, Middlesborough; Frederick Walton, New Seaham, and Jack Cummett and William Clark, Whitby, apprentices [15-year-old orphan boys].

Blackhill: Sunderland Echo, May 10th 1937: The master is Capt. P.F. Ridley

Coquetdale: Sunderland Echo, April 22nd 1937: Captain C. Smith, of Hastings Street, Sunderland. Mr George Pain, of Grange Street South, Sunderland, the chief officer.

Hamsterley: North Mail April XX, 1937: The master of the Tyne ship Hamsterley is Captain A.H. Still, of Estoril, Oaklands, Swalwell, and the others aboard are: J.R. Matthews (1st mate), Roman Avenue, Walker; N. Johnson (2nd mate), Trevor Terrace, North Shields; W. S. Joice (wireless operator), Fitzroy Terrace, Sunderland; W.S. Jones (A.B.) Marsden Street, South Shields; M. Darmody (bosun), Wilson Street, South Shields; S. Stephens (A.B.), Orange Place, South Shields; M Lamport (A.B.), Fawcett Street, South Shields; O. White (A.B.), Fowler Street, South Shields; G. Henderson (seaman), Harper Street, South Shields; A. Hastier (first engineer), Candless Street, South Shields; W. Allam (second engineer), of Sunderland, and W. Usher (donkeyman), Broughton Road, South Shields. The following are firemen: Alidie Ali, John William Street, South Shields; Hassan Abdullah, Grace Street, South Shields; Hassan Ahmed, Commercial Road, South Shields; Ahmed Ali, Derby Street, South Shields; Hassan Yehya, Green Street, South Shields. Cook and steward: John Dryden, Woodbine Avenue, Walker; mess room boy, G. Lyth, The Laws, South Shields. [A donkeyman worked the donkey boiler – the small boiler used by the crew, especially in port.]

Knitsley: Sunderland Echo, April 30th 1937, p1: Knitsley … She has just recently been purchased by Consett Iron Company, and there are a number of Sunderland men aboard her, including Mr Cunliffe, a seaman, and Mr Dougherty, a messroom steward; North Mail, May 6th 1937, p1: Master: Capt. Frederick Robinson, of 14 Hawarden Crescent, [Sunderland]; 17 crew prosecuted June 17th South Shields courts for refusing to sail to Spain without additional payment: John George Wilson, Mitford Street, Fulwell, Sunderland; John Vivian Lloyd, Straker Terrace, Tyne Dock; Thomas Watson, Weir Street, Tyne Dock; and eight others from South Shields: John Robert Lawson, Quarry Lane; Jonathan Williamson, Stainton Street; Robert Duncan, Braeham Street; Thomas Watson Cunliff, Shortridge Street; John Pease, Hardwick Street; Hector McDonald Profit, Campbell Street; John Taylor, Slake Terrace, and Joseph McQuade, H.S. Edward Street.

Stanbrook: Sunderland Echo, April 23rd 1937 p1: Wearsiders in the crew are W.S. Joice (wireless operator), Fitzroy terrace; and W. Allam (seond engineer); North Mail, April 24th 1937: Stanbrook crew included several Tynesiders. Blyth men aboard are P. Halpin, T. Wilson and P. Burns, all firemen, T.B. Rowland, T. Joyce, A.B.’s and ordinary seaman E. Crutchley and M. Willis.

2 Responses to Danger and adventure for Tyne and Wear ships’ crews in the Spanish Civil War