Although we have hundreds of ship models in our collections, only one of them is dazzle painted. The tramp steamer ss Hindustan was launched in July 1917 by Bartram and Sons Ltd., Sunderland and completed for the Hindustan Steam Shipping Co., Newcastle in November 1917. Her building coincided with the adoption of dazzle painting during the First World War and the ship was painted with a dazzle scheme. Consequently our contemporary builder’s model of ss Hindustan was also dazzle painted. The model is currently on display in the shipbuilding gallery at Sunderland Museum.

Dazzle painting was a system developed in 1917 by the British artist, Norman Wilkinson, to confuse German U-boats (submarines) trying to get into position to fire torpedoes. Earlier attempts to reduce ships’ vulnerability to U-boat attack had concentrated on trying to make them invisible, as with land camouflage schemes, but Wilkinson realised that this was impossible at sea. Apart from anything else, however well a ship might be painted to blend in with the seascape, the smoke from her funnel would always give her away. In May 1917 Wilkinson was an officer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, serving with a minesweeping squadron in the English Channel. This experience, when combined with his artist’s understanding of colour and shape led him to develop a radically different paint scheme.

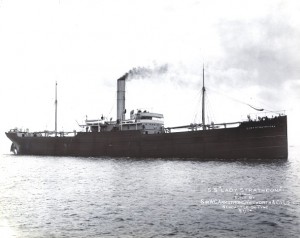

Photograph of ss Lady Strathcona on trials 1904. The problem posed by smoke from the funnel is obvious. Renamed Wairuna she was captured by the German surface raider SMS Wolf and scuttled with explosives 17/06/1917. (TWCMS : G7951G

In July 1919 the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders held a Victory meeting in Newcastle upon Tyne at which Lieutenant – Commander Norman Wilkinson, O.B.E., R.N.V.R., read a paper on “The Dazzle Painting of Ships”. What follows here is largely based on Wilkinson’s paper, illustrated with photographs and objects from Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums’ collections. (1)

Wilkinson’s idea was that, if the silhouette of a ship could be broken up by painting her with contrasting colours and tones so as to destroy her outline and general shape, an attacking submarine would find it difficult to work out her course. The primary object of the scheme was not so much to cause a submarine commander to miss his shot once in position, but to mislead him when the ship was first sighted, as to the correct position to take up. Since a submarine’s maximum underwater speed was low, about 5 knots, it had little chance of taking up a new position if the submarine’s commander had misjudged the direction of a ship making 10 knots or more.

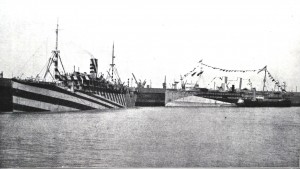

3. Photograph of ss Grantuly Castle (the single funnelled ship to the left), that Wilkinson used in his presentation as a good example of the striped type of dazzle scheme.

Wilkinson made no claim that a dazzle painted ship was certain of escape, but simply that she must be a more difficult proposition to a submarine than an all grey ship. All ships had to be painted for protection from the weather so there was little or no delay caused by the scheme. And it was cheap. No structural alterations were needed and more than 100 vessels could be painted for the cost of one good class cargo ship and cargo.

Wilkinson submitted his scheme to the Admiralty and a trial began immediately with a single ship, HMS Industry. It was quickly realised that larger scale trials would be needed, and, within a few days, 50 transports were ordered to be painted as rapidly as opportunity allowed. Each of these ships was painted differently to prevent the enemy becoming accustomed to any particular design. Some designs were more successful than others and Wilkinson eliminated those which did not give the required distortion. Some time before the end of the war it had been established that the most successful design was the striped type. It was not only the best for breaking up the shape of the ship; it was also practically fool proof in application. This was particularly important in the early stages of the scheme, before a team of officers, many of them artists, had been trained and sent to the ports to supervise the execution of the designs.

Wilkinson observed that, over time, the foremen painters in the shipyards began to understand the thinking behind the scheme and as a result became very interested in the work. This helped greatly when the volume of work increased. Previously, if a scheme for a 380 foot long ship needed to be adapted for a 350 foot ship, an officer would have modified the painting plan. Towards the end of the war the adaption could be left to the foremen painters, which was just as well when as many as 100 vessels were being painted at the same time in one port, with only two or three officers to oversee all the ships.

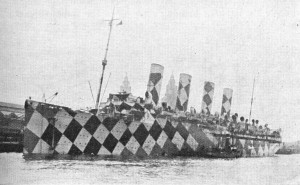

5. Photograph of dazzle painted standard cargo ship ss War Climax on trials September 1918. She survived the First World War but during the Second World War, renamed Rokos, she was wrecked after being bombed at Suda Bay, Crete, 26/05/1941. (TWCMS : 2001.3700-x)

The first designs were developed after a small wooden scale model of each ship was painted with a dazzle design in wash colours, so that it could be swiftly altered. The model was then placed where it could be carefully studied through a submarine periscope. Different sky backgrounds were placed behind the model and the design was altered to obtain the maximum distortion. The Imperial War Museum has hundreds of these simple models in its collection.

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?query=dazzle+paint&items_per_page=10

The final version was given to a plan maker, who transferred it to a 1:16 scale profile plan of the ship on white paper showing port and starboard sides. The plan was then sent to the outport officer where the particular ship was lying.

6. Photograph of dazzle painted Z class anti-submarine patrol boat, based on a whale catcher design. Fifteen of these boats were ordered from Smith’s Dock South Bank shipyard on the Tees in March 1915 to combat the U boat threat. All were completed between August and November 1915. The theory was that ships designed to hunt whales would prove successful submarine hunters. Unfortunately although the Z class boats were very manoeuvrable they were not very seaworthy and no more orders were placed. (TWCMS : 1993.9590 – Smith’s Dock Notable War Jobs album)

Naval vessels were asked to make observations on the appearance of dazzle painted vessels when they were encountered. Through the late summer and autumn of 1917 favourable reports came in confirming the confusing effects of dazzle paint.

Account of the officer of the watch on HMS Martin 27th September 1917

“Sighted Oiler Clam about 9 miles distant, 4 points on starboard bow, and for some time could make nothing of her. When about 5 miles distant I decided it was a tug towing a lighter with a short drift of tow rope. The lighter, towing badly and working up to the windward, appeared to be steering an opposite course. It was not until she was within a mile that I could make out she was one ship, steering a course at right angles, crossing from starboard to port. The dark painted stripes on her after part made her stern appear her bow, and broad cut of green paint amidships looked like a patch of water. The weather was bright and visibility good; this was the best camouflage I have ever seen.”

In October 1917 the Admiralty decided to dazzle paint the whole of the British Mercantile Marine and a considerable number of war vessels employed on convoy and other duty. A memorandum was issued under the Defence of the Realm Act.

INSTRUCTIONS TO “DAZZLE” OFFICERS.

It has been decided to paint all merchant vessels and armed merchant ships, and certain of H.M. ships, with the “dazzle” scheme of painting.

This scheme is based on the principle that invisibility at sea being unattainable, some protection may be afforded by painting ships in such a way as to confuse an enemy submarine, and by causing doubts as to the course, speed and distance, thus delay the discharge of the torpedo and cause uncertainty of aim.

A number of designs are in preparation which will enable a suitable plan to be selected for any particular ship that may come in hand for refit or painting.

Officers are being selected who will represent the Director of Naval Equipment at all the principal shipping ports, and who will be furnished with plans prepared by the Admiralty.

Wilkinson had hesitated to use white paint in the early stages of the scheme, but after considerable experience it was discovered that it was the best “colour” to paint those parts of the ship intended to be invisible. It was also found that the stem and outline of the stern of a ship could be broken up by using colours in strong contrast, always including white. Although it was impossible to obtain invisibility by painting, parts of a vessel could be made relatively invisible by using contrast.

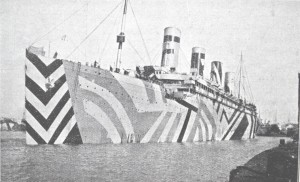

7. Photograph of the port side of RMS Olympic used by Wilkinson. This image illustrates very well the principle of carrying the starboard side design around the bow.

The best way to achieve this was by painting the light parts of a design with two light colours, each with a definite variation in tone. Thus, on the starboard side the vessel was divided in the middle; the fore end was painted white, and the after end pale (no 2) blue. On the port side – fore end pale blue and after end white. But this was the broad principle and was subject to modification. A colour was never allowed to stop at an important constructional point, such as the stem or the centre of the stern. The white on starboard or the blue on port would be carried round the bow until checked by part of the dark pattern, and the same at the stern. Two tones of light colour were used to improve the chances of one of them harmonizing with the sky behind and thus giving great distortion to the vessel when used with black or dark greys.

The simpler the design, the greater degree of distortion achieved. A simple design also reduced the time taken to execute and maintain it. The colours used most frequently were black, white, blue and green, either as they were, or mixed to various tones. Vertical lines were avoided while sloping lines, curves and stripes gave the greater distortion. The output of dazzle painted ships was restricted by the number of skilled painters obtainable and the quantity of paint available. About 320 ships were painted in the North-East Coast area.

8. Photograph of dazzle painted aircraft carrier HMS Furious, probably taken in 1918. Designed as a battlecruiser she was built at Armstrong Whitworth’s High Walker shipyard on the Tyne and modified as an aircraft carrier before completion. Her turbine engines were by the Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Co. Ltd. (TWCMS : 2011.693 – Booklet The Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Co. Ltd. – A 50 Years Retrospect)

Some British warships were dazzle painted, mostly convoying cruisers, destroyers, minelayers and other ships working with merchant vessels.

Warships, which carried very large numbers of men, were painted by their own crews.

One group of British warships, the ‘24’ class of escort sloops, were not only dazzle painted, they were also designed with structural features that would confuse an attacking U boat. In the case of the ‘24’ class (so named because 24 ships of this design were ordered by the Admiralty) they were designed to appear double bowed, with two pointed ends. As a further twist, half the ships were built with the mast forward of the funnel, and half with the mast abaft the funnel. A U-boat that had previously encountered one type was likely to be confused if it later came across the other.

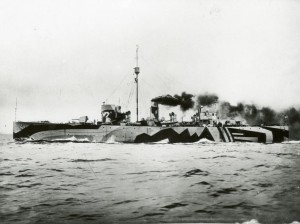

9. Photograph of dazzle painted ‘24’ class sloop HMS Flying Fox on her sea trials. You can see the double bridge arrangement that adds to the confusion, and painted hawse pipe and anchor at the stern are also just about visible. The smoke is a bit of a giveaway, but this is clearly a maximum speed trial and she wouldn’t be making this much smoke when escorting a convoy. (Image courtesy of Ian Rae)

A dazzle painted flotilla of ‘24’ class sloops was based at Queenstown (modern Cobh), in the south of Ireland, where they escorted incoming ships from the North Atlantic and hunted German submarines. HMS Flying Fox, built on the Tyne in the Neptune Yard of Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, was sent to Queenstown in May 1918. This photograph shows that she had her mast forward of her funnel.

Another sloop flotilla was based in Scotland, at Granton, in the Firth of Forth. HMS Ladas, built in Sunderland in 1918 by Osbourne Graham & Co., was sent to the Granton flotilla. Ladas was only completed in November 1918, at the very end of the war, and was never dazzle painted. This photograph of a model of HMS Ladas clearly illustrates the double bow arrangement, with propeller, rudder, and painted anchor and hawse pipe indicating which bow is the stern. Ladas had her mast abaft the funnel, unlike Flying Fox and the other Neptune yard ships, which had their masts forward of the funnel.

Wilkinson concluded that the consensus of opinion was that a large number of ships were saved by the use of dazzle schemes. Even when dazzled ships were torpedoed they were often hit in less vital spots, either right forward or aft, and were more likely to make port.

Photograph of dazzle painted oil tanker Cadillac undergoing repairs at Smith’s Dock yard at North Shields on the River Tyne. Cadillac was built by Palmer’s Ship Building & Iron Co. Ltd., Hebburn-on-Tyne and completed in December 1917. On 7th April 1918 she was torpedoed and damaged by U-53 about 100 miles WSW of Bishop Rock. Cadillac was one of Wilkinson’s dazzle ships that made port after a U boat attack. I think it is a fair bet that the repairs are for the damage caused by U-53’s torpedo. (TWCMS : 1993.9590 – Smith’s Dock Notable War Jobs album)

His last remarks looked at what might happen in any conflict of the future.

“Whether paint will ever play a part in future wars it is difficult to say; but …… I think it would be safe to say that in what I hope will be the dim future, strange looking craft will once more pursue their apparently erratic courses across the sea.”

Sadly, it was only 20 years before the world was once again at war, and Wilkinson, disappointed in his hopes for a long peace, was proved right about a revival in the use of dazzle paint. In World War II some ships were still dazzle painted, although the practice was not as widespread as it had been in the First World War.

- Wilkinson, Norman, The Dazzle Painting of Ships, P237 – 263, Vol IIIV (1918-19), Transactions of the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders.

12 Responses to Dazzle Painting of ships in the First World War and the model of ss Hindustan