On Saturday 7th March, 1829, a little after 10 o’clock, an estimated 20,000 people were on the Town Moor in Newcastle awaiting a gruesome spectacle. They were there to see Jane Jamieson’s execution, sentenced to death for the murder of her mother. Arguably though, her hanging was not to be the most grisly part of her sentence. As part of her punishment, Jane was to be dissected at Surgeons Hall, following her death. This ruling was a provision of the 1752 Murder Act, which stated that “for better preventing the horrid crime of murder” dissection would act as a “further terror and peculiar mark of infamy.”[1]

The Murder Act itself was both a punitive and a practical measure, as surgeons and anatomists had extremely limited access to bodies and as a result had become increasingly reliant on an illicit trade in bodies, often freshly robbed from the grave – the most famous of these ‘body snatchers’ or ‘grave robbers’ being Scotland’s Burke and Hare in the c19th.[2] The most famous illustrated example of dissection can be seen in the work of artist William Hogarth and his engraved series “The Four Stages of Cruelty.” In which, the central character, Tom Nero, suffers the ignominious fate of execution and humiliation on the dissection table after death; the cruel reward for his reprobate behaviour.

If the inducement of terror in criminals, was the intention of the Murder Act then it was extremely successful. The punishment of the surgeon’s knife was often more feared than death itself, not least because it was,

“a disgrace, a humiliation, (and) a final act of indignity.”

William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty. Plate IV in the Series. Image courtesy of http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Four_Stages_of_Cruelty

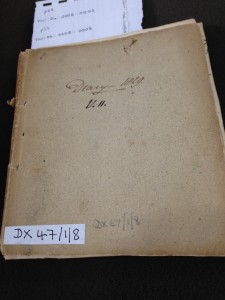

Regional accounts of dissections are rare, often limited to the simple details provided by the records of the Barber Surgeon’s themselves. However, a recently discovered diary of an assistant-surgeon in Newcastle in the 1820’s gives hitherto unprecedented access to such an event. Thomas Giordani Wright was the assistant to Surgeon James McIntyre of Newcastle between 1826-29 and wrote a diary detailing his daily life and works. Amongst Wright’s many entries are several on Jane Jamieson, including her trial, execution and dissection. His entry on her trial is fascinating.

“I could not obtain access to the crowded court but I am told by one who was there that the unfortunate creature is condemned to execution on Saturday morning and to be given to Surgeon’s Hall for dissection. If the latter part of the sentence be correctly reported. I shall most likely partake of the benefits accruing therefrom.”[3]

Wright did indeed “partake of the benefits” as he was one of the many surgeons and surgeons-assistants who attended her dissection and the lecture series that followed. The lectures were given by John Fife, surgeon and later Mayor of Newcastle, and were free to surgeons and their assistants and open to the public for a fee of half a guinea for the whole course, or 2/6 per lecture. Wright thought the best lecture was the one given on Jamieson’s brain at which he estimated about 50 others were in attendance, about a third of whom were non-professionals.

“Mr John Fife on Monday morning gave a very good demonstration on the brain of the criminal who suffered on Saturday….and had a good opportunity, from the freshness of the brain before him, to exhibit its parts and structure in a clear manner, more so than usually falls to the lot of an anatomical teacher.”[4]

A few months after Jane was executed, Wright left for London and thus ended his diaries and with it our fascinating glimpse into medicine and punishment in Georgian Newcastle. Jamieson was to be the last woman hung in public in Newcastle and the last woman hung in Newcastle or Durham for over forty years.[6] The practice of dissecting executed criminals was ended three years later, with the enactment of the Anatomy Act 1832.

[1] The Murder Act 1752 . The same act would introduce another additional punishment, that of gibbeting, an example of a gibbet survives at the South Shields Museum & Art Gallery[1]

[2] There are numerous instances of this practice happening in Newcastle.

[3] Thomas Giordani Wright and Alastair Johnson, Diary of a Doctor: Surgeon’s Assistant in Newcastle 1826-1829, 1St Edition edition (Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle Libraries and Information Service, 1998), 69.

[4] Diary of A Doctor 1826-1829, Tyne and Wear Archives Ref: DX47/1

[5] Ibid entry March 7th Saturday, 1829

[6] Mary Ann Cotton was hanged at Durham Prison on the 24th March 1873

2 Responses to Doctor Death