I’m currently working on the ‘Workshop of the World’ project to catalogue the historic records of Vickers Armstrong and its predecessor companies. This project will make thousands of fascinating documents available to the public for the very first time thanks to a generous grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (made through the National Cataloguing Grants Programme). Included amongst these records is a superb album of photographs taken in the National Projectile Factory, built in Birtley during the First World War.

By May 1915 the British war effort was not going well. It had become clear that the Army was simply not being supplied with the quantity of high explosive shells it needed. The ‘Shell Scandal’ as it became known led to the fall of the Liberal government and its replacement with a coalition. A new Ministry of Munitions was created, with David Lloyd George as Minister and it solved the shell crisis by building new munitions factories across Britain, including one at Birtley, near Gateshead.

These National Projectile Factories needed workers, though, and with so many British men away fighting in the trenches there was a real shortage. This was partly resolved by the large-scale employment of women in the munitions factories but foreign workers also had a key role to play. What made the National Projectile Factory at Birtley so special is that the management and workers there were all Belgian.

The Director General of the factory was a Belgian, Hubert Debauche and the majority of the workforce was made up of Belgian soldiers who had been wounded during the War. Those men were unfit for military service but could still support the war effort through their labour. Significantly they were answerable to their own Government rather than the British. By running it as a Belgian factory, problems such as the language barrier and different working practices between Belgium and Britain were side-stepped.

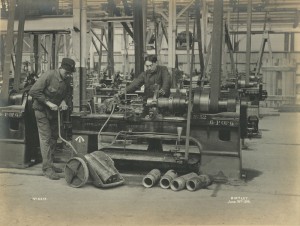

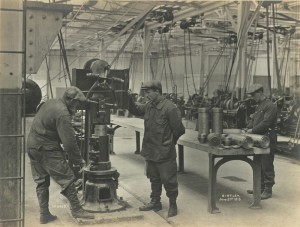

The work in the factory would have been very hard by modern standards – 12 hour shifts, 6 days a week. The workers were still considered to be soldiers and were supposed to wear their military uniform at all times in the factory.

View of two Belgians at work in the National Projectile factory, Birtley, June 1916 (TWAM ref. 1027/271)

This rigid insistence on military discipline by some managers led to a riot by the Belgian workers on 21 December 1916. The trigger was the imprisonment of a worker for wearing a civilian cap when he went to ask for four days leave. The enquiry which followed recommended that military uniform should no longer be worn in the factory or the colony of Elisabethville, where the workers lived.

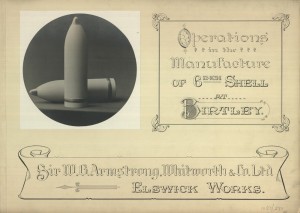

The factory was built and equipped by Armstrong Whitworth and the firm also built their own cartridge factory beside it. Research carried out by John Bygate using Belgian archives suggests that Armstrong Whitworth resisted handing over control of the shell factory but by early 1916 the Belgians had taken charge. The firm obviously maintained an interest in the factory, though, as the photograph album in the Vickers Armstrong collection testifies. The photographs were taken in June 1916, shortly after the factory became operational. The images show the Belgian workers carrying out various processes involved in shell production.

All the images in the album have been digitised and are available online in a new Flickr set.

No attempt was made to assimilate the Belgian workers and their families into the local community. Instead, a separate village known as Elisabethville was established on the northern edge of Birtley, named after the Belgian Queen Elisabeth. The entrance to the Colony was opposite the pub, the Three Tuns.

The buildings were all prefabricated, with accommodation consisting of nearly 900 two and three-bedroomed cottages for families and 22 barracks for single men. The village was fenced off from the rest of Birtley and had its own police force or ‘gendarmes’ as they were called, who could deal with minor offences. Elisabethville had the facilities you would expect of a normal village – shops, a school, a hospital and a church.

At its height Elisabethville was home to around 6,000 Belgian men, women and children. After the signing of the Armistice in November 1918 the Belgians were repatriated back to their homeland and memories of what had happened at Elisabethville slowly began to fade. The album, though, is a reminder of a fascinating episode in North East history and we’re delighted to be able to share it with you. It’s also a testimony to the remarkable achievements of the Belgian workers, many of them left disabled by the War, who produced their shells at a faster rate than any other factory in the country.

You can find out much more about the Birtley Belgians in the book ‘Of Arms and the Heroes’ by John G. Bygate. Useful information can also be found in the recent publication by Brian Armstrong ‘They made ammunition at Birtley’, published by BAE Systems. Reference copies of both are available in the Archives searchroom. Details of our location and opening times can be found on our website.

Visit the Wor Life website for more about our events and exhibitions relating to the First World War.

25 Responses to First World War Stories: The Birtley Belgians