Every so often you come across a story so extraordinary that you can barely believe it really happened. Such is the saga of the ss Baikal, which I stumbled upon whilst innocently cataloguing a box of old photographs…

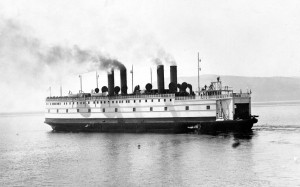

By 1895 construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway was approaching Lake Baikal, but with the Circum-Baikal section years away from completion another way had to be found to fill the 40 mile gap across the world’s deepest lake, landlocked in the middle of the Eurasian continent. The answer? An icebreaking train ferry, to be delivered cross country in thousands of pieces and rebuilt on the lakeshore! So the Russian government ordered the ss Baikal from Sir WG Armstrong, Mitchell & Company on December 31st 1895. This awesome vessel was built of steel 1 inch thick, was 290 feet long and 57 feet wide, and had three railway tracks on its deck for 25 carriages with accommodation above for passengers and crew.

Work on the hull (yard number 647) started immediately at Armstrong’s Low Walker yard and was finished by June. One side of the ship was painted white, the other black, and every part was stamped and marked with paint. Amazingly, it was then stripped back down into 6,900 parts which were shipped to St Petersburg and then carried 5,000 miles overland to Lake Baikal for reassembly!

The engines and boilers were built by Wigham Richardson & Company (as yard number 325) at their nearby Neptune Yard. These were also colour-coded and stripped down, and shipped out in December 1896.

Newly-completed engines (left) and boilers (right) at Neptune Yard ready to be dismantled for transport.

In August 1897, Armstrong’s Chief Constructor, the intrepid Andrew Douie, travelled by rail as far as Krasnoyarsk and then made the final 700 mile trek by horse-drawn carriage (tarantass) to Listvyanka, near the mouth of the River Angara, where a shipyard was being built on the lakeshore. More Tyneside men followed; here’s Wallsend Slipway engineer Mr Handy travelling by sledge after the onset of winter:-

Many parts had arrived at Baikal by November 1897, and the keel was laid in January, but then work stopped as the Siberian winter really started to bite.

Strangely, winter was a good time for pile driving out in the lake, by a process known as “freezing out”: You dig down through the ice until you’re a few inches from the water, then you pause while the ice beneath you thickens downwards. Then you dig down further, pause some more, dig some more, until you reach the lake bed. By this method the slipway was piled out from the shore without anyone getting wet!

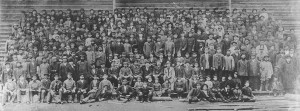

Work recommenced in April but the last parts didn’t complete their long trek from Tyneside until November 1898. The lack of labour-saving machinery (overhead cranes, steam winches, &c.) meant that the ship had to be reassembled using whatever structures they could make from the surrounding trees, and lots more labour was required.

Leading the project were an English chief superintendent, foremen (plater, riveter, caulker and carpenter), and chief engineer. At first, local craftsmen were hired and trained, many of whom were exiles (or descendants of exiles) from western Russia. (It was probably best not ask too many questions; there was that time Chief Engineer Isaac O’Henry learnt that his guide on a long walk in the icy wilderness had previously slaughtered his entire family with an axe…) Things looked up when a Russian manager and workers arrived from St Petersburg in the autumn of 1898, but their much higher wages soon led to ill-feeling, bloodshed and murder.

And yet somehow, after 1 ½ years’ hard labour, the ss Baikal was launched into the lake on June 29th 1899. Mr Douie noted that “The three following days were proclaimed as holidays, and as a natural sequel to the launch the whole of the village was in a state of drunkenness for the remainder of the week.”

By February 1900, Baikal was successfully ploughing through ice 4 to 5 feet thick, though she was not finally fully completed until early summer, 2 ½ years after the keel was laid at Listvyanka.

Meanwhile, a smaller icebreaking ferry for passengers and cargo had been ordered from the same builders and was reassembled at Listvyanka on Baikal’s old slipway.

This ship, the ss Angara, was finished much more quickly and in August 1900 took her place alongside Baikal running two return trips a day between Port Baikal and Mysovaya.

But after all this effort…the railway around the lake was opened in 1905! However, the new line was often blocked by landslides so the ferries were kept in reserve.

Then, in 1918, during the Civil War which followed the Revolution, Baikal was armed with machine guns and cannon by the Red Army but was shelled by the White Russians and burnt out at Mysovaya in August. She was towed across to Port Baikal one last time in 1920 and broken up about 1926. Angara’s story is happier; she worked until 1962 and is now a museum ship in Irkutsk, a fine monument to Tyneside engineering and the hardy determination of the Siberian workforce.

Here in Discovery Museum, Baikal herself is remembered in more than just photographs and plans; amongst our phenomenal collection of shipbuilders’ models is Armstrong’s original 1896 model of Baikal, 6 feet long and built partly cutaway to show the railway carriages inside. It’s on permanent display in our Tyneside Challenge gallery.

As Tyneside challenges go, the supply of these two ships to Lake Baikal was proper epic! That it was achieved so successfully is, to me, an amazing testament to the unstoppable can-do spirit of Victorian Tyneside.