And your starter for ten this week is …. What do the following British 20th Century artists all have in common? – Clifford Rowe, James Boswell, Carel Weight, James Holland, Edward Ardizzone, Pearl Binder, Eric Gill, Victor Pasmore and Ben Nicholson?

And your starter for ten this week is …. What do the following British 20th Century artists all have in common? – Clifford Rowe, James Boswell, Carel Weight, James Holland, Edward Ardizzone, Pearl Binder, Eric Gill, Victor Pasmore and Ben Nicholson?

No? Okay- time’s up! Well, if you didn’t know, they were all involved in some way, be it as founding members or contributing artists, to an organisation called The Artists’ International Association, which was set up in 1933 in London by a group of like-minded radically left-wing artists, in a decade which was to see the Great Depression, Stalinism, the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, the Spanish Civil War and the subsequent emergence of Franco, and finally the outbreak of the Second World War. The principal founders of the A.I.A., as it was more commonly known, included Misha Black, James Boswell, Clifford Rowe and Pearl Binder, and the guiding ethos was to promote a radical response to these events in the art world. James Boswell, in an interview for Donald Drew Egbert’s book Social Radicalism in the Arts: Western Europe (1970) amusingly describes the movement as: “…a mixture of agit-prop body, Marxist discussion group, exhibitions organiser and anti-war, anti-fascist outfit.”

In the Movement’s First Statement of Aims, published in International Literature in 1934 it set itself out as: “The International Unity of Artists Against Imperialist War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial Oppression” and aimed to: “execute posters, illustrations, cartoon, book jackets, banners….” as well as: “the spreading of propaganda by means of exhibitions, the Press, lectures and meetings” and “the maintaining of contact with similar groups already existing in 16 other countries.”

Grand aims indeed, but the Association did manage to become highly successful in attracting other leading painters and sculptors to participate in and contribute to their activities throughout its 38 year history, organising many events and exhibitions, conferences, lectures, campaigns and regular meetings of national and regional groups, plus a Lending Library; in 1947, it acquired permanent premises in Lisle Street, London which it maintained up to the dissolving of the Association in 1971, although it had ceased officially to be a political organisation some 20 years prior to this.

A few months ago at the Laing Art Gallery here in Newcastle, I was handed a set of 21 prints to catalogue which bore the imprint of ‘A.I.A. Everyman Prints’ and had been purchased by the Laing sometime in 1940. The prints were part of a set of 52 produced by the A.I.A. in 1940 as an attempt to bypass the traditionally costly practice of producing limited editions of art works, and in the same way that Allen Lane pioneered the mass-market production of quality literature with Penguin Books some four years earlier, the Everyman Prints were conceived of as bringing the work of established artists to a wider, hopefully working-class, clientele: in the same breathless tones that might have been used a decade later to introduce a new-fangled vacuum cleaner or a set of Encyclopaedia Britannica to the postwar public, a magazine advert produced by the A.I.A. to advertise the prints claimed:

“A.I.A. Everyman Prints are intended for every home. To-day, thanks to cheap production of books and gramophone records, everyone can cultivate a personal taste in what they read and what music they hear. Everyman prints now widen the range from which the visual taste can be gratified, by offering the direct work of living artists at a price so reasonable that the outlay need not involve anxious consideration….”

Admittedly, the quality of the paper was obviously a lot lower than would be expected of a conventional art print, as the copies we have at the Laing will testify, but they were produced cheaply and in large quantities by offset lithography direct from the artists’ plates. The majority of the prints were in monochrome, and these were priced at 1/-, the coloured ones selling for 1/6d, and, as with the original Penguin Books, which had been sold for sixpence in high street stores such as Woolworths, the A.I.A avoided selling the Everyman Prints in art galleries, instead making arrangements, for example, to sell them at a number of branches of Marks and Spencer, straight over the counter. They were also exhibited in simultaneous exhibitions in London, Bristol and Durham, as well as featuring in a touring exhibition.

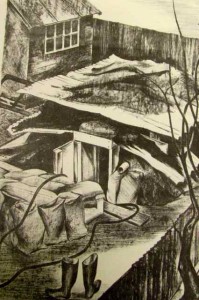

While the above magazine advert markets the prints in a bright, consumerist fashion, what the public were actually getting in 1939 was a much more bleak and realist affair. The print featured in the picture, one of the 21 bought by the Laing Art Gallery, and entitled ‘A Garden—God wot’! is by Maurice de Sausmarez, and, in showing a surburban garden which has been rudely disturbed by the construction of a somewhat grander version of an Anderson Shelter, it typifies the overriding motifs of all the prints in this series: the depiction of the disruption caused to British daily life and the pre-war urban and rural landscape of Britain as a result of the build up to and arrival of War in 1938-39. The artists involved in this series portray some strange juxtapositions in the harsh realism of the measures taken to prepare for war and the civil defence of the country at the time, while, unsurprisingly, echoing what would be the critical morale-boosting aims of subsequent wartime propaganda, namely to show a Britain where, in spite of everything that has changed, it is still “business as usual”. Hence other Everyman prints depict barrage balloons ascending over the roofs and back gardens of Hampstead, the blackout in a family home, evacuees and Home Guards at a railway station, as well as an early wartime football match. I hope to feature one or two of these in future posts.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/

The Story of the A.I.A. 1933-1953 by Lynda Morris and Robert Radford, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1983.